When one takes a look at David Lynch’s filmography both before and after Twin Peaks, it’s even more difficult to believe that something like the director’s surreal, genre-bending small screen soap opera, co-created with Mark Frost, ever existed in the first place, let alone achieved fleeting mainstream breakthrough.

After all, Lynch is rightly regarded as the preeminent American cinematic auteur of his generation — a purveyor of uncanny and frequently unnerving worlds that juggle and blend surface familiarity with hidden seams of danger and violence.

But was Lynch always destined to be an artist who inspired passionate cineastes, yet enjoyed only a few surprise flashes of commercial success? Or did the rocky aftermath of Twin Peaks’ bright-burning initial run, plus the reception of his subsequent movies, send Lynch down a road even less traveled?

In his new book Lost Highway: The Fist of Love, author Scott Ryan interviews several of the onscreen talent and behind-the-scenes players involved in Lynch’s titular psychological thriller, compellingly advancing an argument that the movie is the most overlooked work in the director’s estimable canon, and also maybe the most intentional, if not first, step in the direction toward how he is now regarded.

The first of three Lynch films set in and around Los Angeles, Lost Highway is split roughly into two halves, and changes out protagonists in a manner that confounded a lot of viewers and critics at the time of its 1997 release. What Lynch didn’t say publicly at the time was that he — very much like a lot of America — was interested in the O.J. Simpson murder trial. In particular, Lynch was fascinated by how the human brain seals off certain traumatic incidents. This informed the story he set out to tell, co-written with Wild at Heart collaborator Barry Gifford.

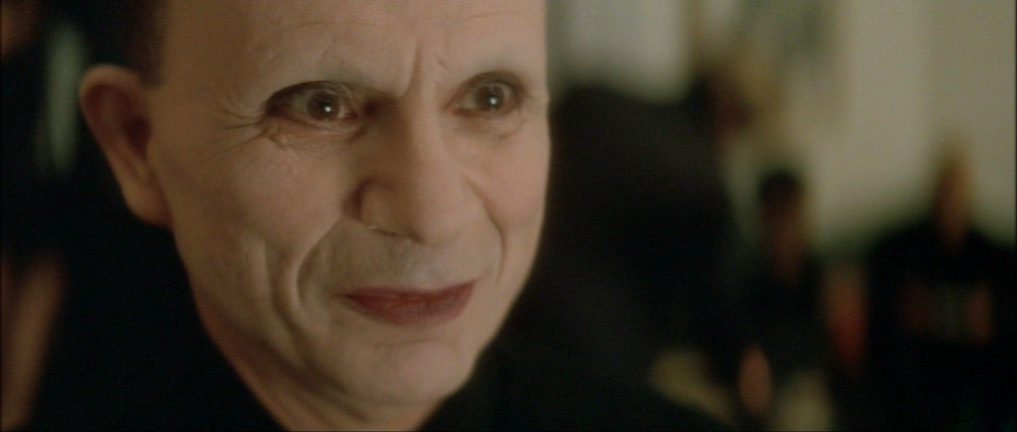

Lost Highway opens with saxophonist Fred Madison (Bill Pullman) and his wife Renee (Patricia Arquette) receiving a mysterious VHS tape on their porch one morning. When they watch it, they see grainy footage of their house. After another tape arrives revealing indoor shots, including of the couple in bed, they phone the police. After a creepy encounter with a pale-faced Mystery Man (Robert Blake) at a party, the couple returns home. The next morning, a third tape shows Fred crouched over Renee’s dismembered body.

Convicted of murder, Fred is sentenced to death row, where he is beset by intense migraines. One day, guards discover Fred to be missing, somehow replaced by auto mechanic Pete Dayton (Balthazar Getty). After Pete is released from prison, he embarks upon an affair with Alice Wakefield (Arquette again), the mistress of a menacing gangster, Mr. Eddy (Robert Loggia). Free-floating intrigue and dark consequences ensue.

From his home in Florida, Ryan, the managing editor and creative director of The Blue Rose Magazine whose additional work includes Moonlighting: An Oral History and last year’s Fire Walk With Me: Your Laura Disappeared, recently took some time to connect via Zoom with Brent Simon, and discuss his new book. Their conversation is excerpted below, edited for length and clarity.

Question: The book very substantively addresses… the power of Renee/Alice, which was absent many readings upon its initial release. You talk very candidly about turning off the film when you first viewed it in 1997, but when you revisited it, did that immediately strike you in your first read of the film, or was it in the interview with Patricia Arquette where she talks about Alice being a monster?

Scott Ryan: I had already had those thoughts before I did the interview with Patricia Arquette. What was incredible to me was that she backed up what I suspected. Now, you never really know, because it has to come from her, but all that I knew is that there’s one little quote on a making-of featurette for Lost Highway where Patricia Arquette says, “I called David Satan while we were filming.” And I was wow, because you don’t hear his actors say that. Every actor says he’s the greatest, he’s the most wonderful, I’d do anything for him, and here we had someone in 1997 calling him Satan and I thought, “Oh, we gotta bring this up!” But then she brought everything up, and I didn’t even have to. She felt that Alice was a monster, which is to me the most impressive thing that comes from my book. I don’t think anyone has ever said that anywhere, and to hear it from the person who created that character (was amazing), because you think of Robert Blake being the monster, or Robert Loggia, or Bill Pullman, not Patrica Arquette. If a man said that, we might all be in trouble. But here’s a woman saying that no, she’s manipulating Pete, which is Balthazar Getty, but it all is a fantasy from a man, so it does roll back to this misogynistic take… and already people are tuning out from this interview, because it’s too complex! (laughs) But that is the complexity of Lost Highway — you can’t just sit down as a critic and say, “Lynch is a misogynist, this is horrible, look what he did to Patrica Arquette!” You have to have a longer conversation. And she did eventually say, “I didn’t really think he was Satan.” (laughs)

Question: This is a good pivot point to the interstitial scene where Pete is in the backyard looking over the fence. In the recesses of my mind this shot was maybe two or three seconds, but it seemed much more substantive when I saw the film again in its 4K restoration last year, in a way that still perhaps remained a little bit out of reach, interpretatively. I’m curious your impressions of that scene, and what if anything you feel it symbolizes.

Scott Ryan: Well, to me, what I got out of it this time is that that is the opening credits. I mean, you’re now watching a new film, and when you look at it like that you can so see that — now, they’re not going to be the fast, shooting yellow dart credits (of the movie’s real opening). It would have a nicer font and slower fade in and fade out, and that background music is a completely different thing than the Bowie song (“I’m Deranged”), which is coming at you — he’s deranged, and there’s all this kinetic energy. This is instead a little Latin beat, there’s a Sunday morning (vibe), the guitars are nice. And I think for Lynch — and it didn’t work then, but I think it works now — it’s a palate cleanser: forget about what you saw, we’re going to start over, now here’s another story. And now I know from Balthazar that he didn’t think it connected to the story at all, he’s the real guy in the thing, and that’s what they’re doing.

Question: In the book you talk to (cinematographer) Peter Deming and (camera operator) Scott Ressler, among others, and get into lens-whacking and some of the in-camera effects used in the movie. Dating all the way back to Eraserhead, David Lynch really loves the DIY elements of filmmaking — he wants to mess with those things himself, and he’s not always aiming for something that totally blends in.

Scott Ryan: Well, I think you can go all the way back to the bird in Blue Velvet, too, which I think at the time, when effects were not that great, people were like, “Well that’s the fakest-looking bird I’ve ever seen.” That was on purpose — he’s doing that. It wasn’t a bad effect. They could have gotten a bird — of course they could’ve gotten a bird! He wanted a mechanical bird because he loves that. In interviewing George Griffith, who plays Ray in The Return, he talked about what it was like to lay on the floor of the Red Room and have David sit above him and place the blood and how it’s going to be and where it’s going to go and talk with (makeup artist) Debbie Zoller about it. He was like, “I was a piece of canvas.” There are special effects in The Return, there’s no doubt about it — all of part eight, with the atomic bomb — but it is the in-camera stuff where you really feel Lynch. And you kind of see that in the bonus features of The Return, where Kyle MacLachlan does a knee thing to fall down through the air, where they could just cut him out. But that’s what Lynch wants to do. And I think it makes a difference — I think it feels different when it happens in-camera, and you get (more) caught up in the story. I could be wrong, it could be where I come from, but when I see one of these total special effects movies I just feel like I’m watching a video game, and not a story.

Question: The deep loyalty that Lynch inspires from almost everybody that works with him, from actors to crew — where do you think that comes from? A lot of people speak not just fondly of the time working together, but with a certain guardedness, maybe.

Scott Ryan: For me, that was the fun of interviewing Deepak (Nayar), who hasn’t worked with David since Lost Highway. He would just tell stories. The worst interviews you get are people who worked on The Return, because they’re still afraid of the NDAs and they don’t want to say anything. And you’re like, “Man, we’re not trying to give away the store here, we’re just trying to learn and document it while we’re all still here.” So there’s always that balance, and this is probably going to end up being more about me than David, (laughs) but I think it’s kindness. I think when you are kind, and you’re at the top of the pyramid, that kindness rolls all the way down. When you’re at the top of the pyramid and you’re a bully and you’re mean, that rolls down (too), and that’s how everyone treats everyone. So if we just take lens-whacking: Scott Ressler, who is not just the cameraman but he’s down the totem-pole, he heard David and Peter talking about if there was only a way to get blurry and then pop back (into focus), and he just went up and said, “Well, I could just pull the lens out and put it back in,” and David said let’s do it. But if David said, “Hey, I’m talking to my DP, you get back in the corner,” then everyone is going (to notice and react to that), the costume person isn’t going to say, “Hey, we should do her nails a different color every time.” David I think is open to everything. Everyone says that. Therefore everyone gives ideas and they want to work with him again, because some of those ideas are in the movie. I think David, because he meditates, puts kindness first, and so he gets kindness back. I can’t say, because I don’t know him. But from interviewing the people he’s worked with, I just get kindness from him.

Question: Fred has a line in the movie about liking to remember things his own way versus how they happened. In your own work, did this book make you reflect upon your own relationship to memory, and how reliable some of those deeply held memories in fact are?

Scott Ryan: To me, that is the most important line in the film. I feel like you could go through each of Lynch’s films and (there) would be one line that would explain the movie. I do think he does that, and I used to be able to kind of say them a little bit, and now I forget. I should write them down, especially as a writer. For me, my Fire Walk With Me book was almost all memory — I tell a ton of stories because I’ve carried that movie with me. On this one, I just tell one story that I remember from watching the movie the first time. But I think that’s what happens with good art — that yes, you consume the art and you think about the art, but what really happens is that it melds with your day that day. I remember going to see Mulholland Drive in the theater the day it came out, and I remember watching The Return that first night. I wasn’t at my house, I was at my friend’s house, but I can picture the couch and I know the kid who was sitting on the floor over there. When you have those moments, art can be burnt right in with you, and you can’t separate it anymore. So is it memory? Is it fact? Did it happen? I don’t think it even matters anymore. It just becomes your lore. How’s that for a highfalutin answer? (laughs) But I just believe it — especially for me, where movies and music and television matters to me more than some personal relationships. You carry those longer than most of your friends.

Question: They’re seared into you, for sure. And then sometimes you re-explore those at a different time in your life.

Scott Ryan: I’m going to ask you a question, because something I find fascinating is the idea of nostalgia. People tell me, “You just like that because you’re nostalgic about it.” I don’t think that’s true. Do you really watch Indiana Jones because you wish you were 12 and playing in the backyard? No, I don’t think so. If the movie was crap, you’d say I watched it when I was 12 and I’m over it. There has to be something in that art that draws you back. And Lynch’s work is always going to draw you back.

Question: We maybe have something shared innately within us that predisposes us to that. I was never the kid who was interested in watching Star Wars or Indiana Jones five, 10, 15 or 20 times. I was always more interested in seeing something new, which I think was atypical for my age.

Scott Ryan: I gave up animation after Finding Nemo. I’ve never watched any animated movies since then. I really liked Finding Nemo, I thought it was good, and I also thought, “I’m over animation”. I loved Aladdin and Beauty and the Beast and The Little Mermaid at that time, and I haven’t watched any of them in years and I’m going to go to the grave without going back, because I don’t think I’m going to get something from it like I did when I was in my early 20s and they came out and it was a big deal. But I want something that’s going to challenge me. There are different kinds of things, but that’s what I’m searching for — something that lights my fire like Twin Peaks did.

Question: What was the biggest lift for the book, the thing that involved the most research?

Scott Ryan: It’s weird, because I think the hardest part was how to end the book, to be honest. I’d really counted on getting Bill Pullman, because I wanted to start with Patricia Arquette and end with Bill Pullman. That’s how I set the book up when I mapped it out, and I put the soundtrack as the halfway point. And then I wasn’t going to get Bill Pullman. I knew it wasn’t going to happen, and then I was like how am I going to end this? That’s when I stumbled upon Jack Nance, and making it more of a Lynch ending than a Lost Highway ending, and getting (actress) Charlotte Stewart involved, and (I Don’t Know Jack director) Richard Green and people who knew him, Mark Frost and things like that. That was the hardest part — having a semi-emotional ending… a satisfying ending, because the film doesn’t have a satisfying ending. I probably worked the hardest on that last chapter, getting the right tone, to be final.

Question: It’s really touching, because you get a sense of people’s love for Jack that is articulated within their stories… but it’s also lined in a very bittersweet way, because what happened to him was tragic, and many of them tried to pull him out of it.

Scott Ryan: It helped me feel like this could end the book, and we get almost another mystery about what happened to Jack and why was he at this place and what did he say — we’ll never know (all the answers to) those questions, and it just mixes in with the mysteries of Lost Highway. And whenever you finish a book, you’re like, “Well of course that’s the end,” but at the time I was like how am I putting this one out, because the last book is just rolling to the Sheryl Lee interview and I knew I had that, and that has an arc. But in this one, for a while I was scared.

Question: The Debbie Zoller interview was quite interesting, and spotlights a craft frequently ignored or under-appreciated. How much prep did you do with that?

Scott Ryan: With Debbie I sent her pictures, which is sort of the way I’ve been doing the last two books, which is a good way to do it. So I made it as easy as possible for her to take a look and walk through. Now what I didn’t know is that she was going to remember every single thing. And I don’t know, I don’t want to overstate it, but she actually became a hero to me, because I don’t know anything about make-up, and I don’t know anything about color. I’m the worst when someone says what color is this or should this go with that or what do I wear. I don’t know any of that. But I love craft, and she is the best at her craft. And I learned so much in that interview, because she’s so smart, and I also love smart women, which is why I love the Patricia Arquette interview, and they’re great friends. And it all rolled together. I don’t know how people feel about it, but to me with the cameraman, the DP, the make-up artist — you get more there I think than from an actor who just embodied and said words that other people wrote down. I’m not diminishing them, but I’m just saying there’s a lot of craft in a film — it’s not just Brad Pitt or Tom Hanks or whomever.

Question: Particularly when it’s reaching for something different, when it’s a project that has ambition and has someone at its helm who is collaborative by nature — the way I think that Debbie is able to articulate things that aren’t simple ideas or choices, just very minute details and the manifestations and ramifications of those was fascinating.

Scott Ryan: Yeah, down to, for example, I was so curious about Patricia Arquette’s lips. When she first comes to the garage she’s wearing a silver dress — or again, I would say silver, and Debbie would say well it’s actually metallic number seven or whatever, I just don’t know those things — and it seemed like her eyeshadow matched the dress, but also a tinge on her lips. And then I learned yeah, (Debbie) would take the eyeshadow and brush it on her lips because she was matching everything down. That is a level of detail that I just don’t know that you’re getting in Spider-Man 17.

To order Lost Highway: The Fist of Love, click here. Additionally, there will be a very special screening of Lost Highway in Los Angeles at the Lumiere Cinema at Music Hall on Saturday, June 24, at 7:30pm — following a screening of Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me on Friday, June 23. Each screening will be followed by a Q&A hosted by Twin Peaks: The Return star George Griffith, and special guests will be present each evening. For more information, click here.