Sometimes the best way for people to overcome their previous agony, especially from when they were children, is to embark on an emotional journey that allows them to fully contemplate the effects of that past trauma. The new character-driven docseries, ‘The Fourth Wall,’ delves into the painful effects caused by the now defunct New York cult, the Sullivanians, on its former members over the course of four poignant episodes.

The show was written by Keith Newton and Luke Meyer, the latter of whom also served as the director. The duo also served as two of ‘The Fourth Wall’s executive producers. Several of the survivors from the cult, including Amy Siskind, Artie Honan, Jesse Lambert and Karen Bray, as well as Newton, appear in the documentary.

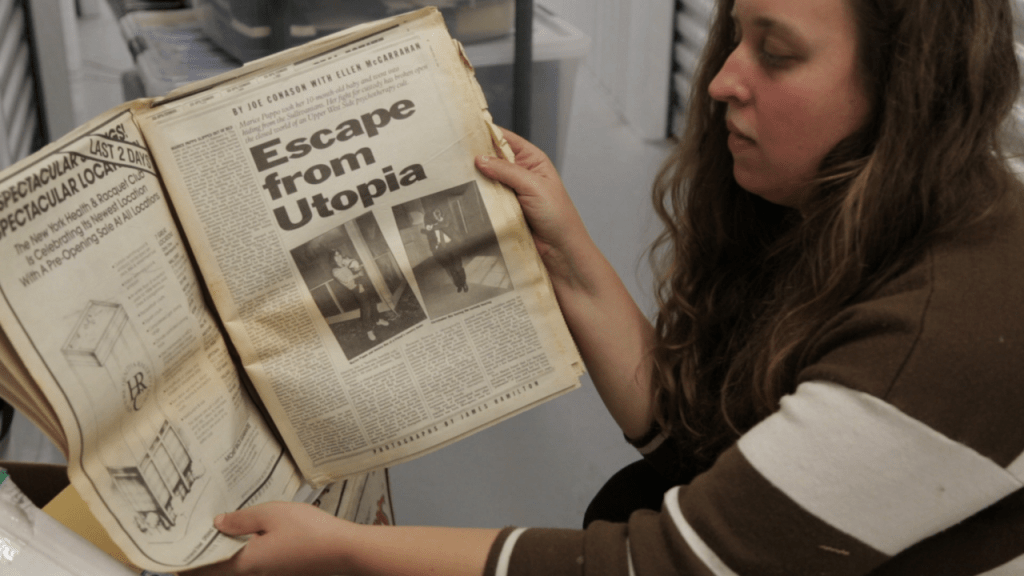

‘The Fourth Wall’ Newton, the son of former leaders of the Sullivanians, as he investigates the transgressive group he was raised inside of, as he discovers long-buried secrets about the truth of his childhood. The secretive psychotherapy sex cult was hidden in plain sight on Manhattan’s Upper West Side in the 1970s and ’80s, thriving underground from its utopian heyday to its dramatic collapse in 1991.

This history has never before reached a public audience in such a complete and dramatic form as captured in the docuseries, which moves beyond the typical cult-narrative to explore the emotional fallout for perpetrators as well as victims. The project’s four episodes reveal the trauma, guilt and healing of those who were involved. Through intimate and exclusive access to the former members, therapists, and children of the group, series creators Newton and Meyer unpack an emotional journey that reverberates across decades, leading to the cult’s haunting and unpredictable aftermath.

‘The Fourth Wall’ had its World Premiere during the Indie Episodic (NOW) section of last month’s Tribeca Festival. During the festival, Meyer, Newton, Siskind, Honan, Lambert and Bray all generously took the time to talk about making the documentary together during a roundtable interview.

Question (Q): Which conflicts were crucial to develop early on in ‘The Fourth Wall’ to get people invested in what’s happening? How did you also develop the pacing while you were telling these conflicts in each episode?

Luke Meyer (LM): Basically, all of the conflicts across all of the episodes have to do with the friction between the past and the present. But as seen at the end of the first episode, some of the narrative that Keith’s mother Helen had been giving him is being challenged very strongly. At the end, you see her understanding that what the group was for her is something that other people don’t agree with from then on out. So that’s a big point of conflict for her storyline throughout the series.

There are also other people trying to to come to terms with their understanding of the things that they did in the past. So it really is a question of how what happened before affects what life is now. That’s a major conflict that we focused on in the series.

Keith Newton (KN): To add to that, the way that the conflict between me and Helen, my mother, plays out over the whole series is indictive of the conflict between alternate versions of reality. You can say it’s truth versus lies versus falsehoods.

But I think that’s oversimplifying it. I think that different people want to tell different stories about the past and their own lives. Those stories come in conflict with each other. My mom and I have this central version of that.

But different characters and subjects across the series have versions of that in their own way. There are family relationships that are so complicated by the group or by the people themselves. There are people who are conflicted with themselves about which version of their own lives they want to hold onto and feels most true to them.

In this first episode, we really tried to set up the reality that The Fourth Wall really was this liberating, ideal place at first. But a lot changed over time. We felt it was really important to establish that because it informs people’s experiences over all these years as they debated in their minds, was this good or was this bad? Was I completely coerced to join this, or did I choose it on my own free will? All of those things are constant negotiation over time.

I think Artie can speak to that. Also, Karen, whose story doesn’t appear in the first episode, but we dive into in the second episode, and Jesse as well, can dive into that, too, in very different ways.

Artie Honan (AH): Not only can people debate it in their minds, but many of us can also discuss it, as we’ve stayed friends after the group ended 30 years ago. I’m still close friends with many of my roommates from the 1980s.

One of the topics in our discussions about the series was whether Keith was going to be able to deal with how people have felt about his mother. It was almost like people were taking bets.

Karen Bray (KB): My mother isn’t in this series because she would rather be dead than discuss anything about it publicly, except with her close friends. The fact that she’s so hesitant to talk at all has affected me and what I have said publicly. So I admire that Keith has confronted this in this way.

KN: The series’ central conflict is with my mom because she encapsulates so many of these things we’re talking about. She is – and was – a loving mother, but she was also a leader in this group, which put us in this situation. Many of the decisions she’s made affected all of these other people’s lives.

The question of my paternity evolves over the series. Things come out about that that involve other people, whose lives were deeply affected by how babies were conceived and how children were raised. That became central to the trajectory of the series.

Q: What was the process like of selecting the archival footage from the Sullivanians’ history that would be included in thedocucseries?

LM: One thing that we were dealing with when we were telling the story was having a limited amount of coverage, and in some cases, there was literally nothing. For instance, there are no images of a therapy session because they were private.

But we worked with this amazing archival producer. She found a ton of different sources, including when a Soviet news crew came and covered the group in the early ‘80s. That footage hadn’t been available in this country until we sourced it. So that’s in the series.

We also wanted to show the intensity of what was going on in the place. But for some of those clips, we didn’t have the source recordings for them

We also sourced period appropriate, atmospheric footage that lends to the idea of what therapy sessions would look like, or what New York City looked like, during that time, and things of that nature. That way people’s imaginations could follow what we were showing

KN: Just to go back to what Luke said about the conflict between the past and the present…the original core of our archive were things that I collected from my childhood, including images that I held onto for years, not knowing what I would ever do with them. But it felt like I had been doing it for some purpose.

When we have the tabletop when you see our hands moving around the photographs, it was a tangible relationship to the past. So many ways in which we engage with the archives, or at least we tried to, were very visceral.

When Jesse and I go to visit the summer house Upstate, and being able to be back in the physical place and engage with it in this really tangible way, was helpful. One of the themes of this series is how you engage with the past and remember things, and how your memory changes over time, and how you interpret things differently.

So much of what happened in the therapy sessions at The Fourth Wall was that so many people’s stories were instructed for them by their therapist. The first thing you did was take your history. So you would give your whole life story to your therapist, and the therapist would interpret and analyze it and rearrange it, and then give it back to you in a different way. So the idea of how you tell your own story and how you engage with your own past, is crucial.

As people left the group, as Artie described, they stayed friends. But they’d have to look back and look into their past in The Fourth Wall, as well as their earlier past, in a new way, so that they can reconstruct it for themselves. So the archive was always trying to speak to them.

Q: What was your strategy to reaching out to Fourth Wall members? Did you want to reach as many members as possible by any means possible?

KN: I’d be curious to hear what some of the subjects have to say about how we reached out to them.

But the answer is really different for everyone. It was an extremely sensitive experience, which is why this process took so many years. We did it very slowly and by person by person. In ways, it was very personal and very specific to each individual, knowing what their story was.

We did try to cast the net widely. We did some outreach in which we sent open letters to everybody we knew from the group. But we didn’t push people who didn’t respond to us, or we knew didn’t want to have anything to do with us.

So we didn’t feel like we needed everyone, but we did feel like we needed a representative from each group. We felt like we needed a therapist, as well as kids from the group and people who felt like they needed to justify and defend things from the group. We also needed people who felt like this was the absolute most destructive thing that has ever happened to them. We also wanted to speak with people who escaped the group earlier on, and those who stayed until the end.

So it was a very complex experience, but we felt like we needed to cover all of that ground. When we felt like we had certain things told, we’d then push at other people who could tell other sides of the story.

LM: I wasn’t involved in reaching out in the same way you were, but I felt like a lot of it happened organically. One person would express some interest, and then they would connect us with another person

KN: Jesse was the first person I talked to about the series. Somehow we ended up at our go-to, one of the classic New York Jewish delis. We met about four times at the 2nd Ave. Deli and we talked this all out. I couldn’t have done it without that whole process. As things evolved, it could be over email or a phone call.

Jesse Lambert (JL): I would like to say something about that, too. During one of those early conversations, which was back as early as 2013. I remember when you first told me that you wanted to work on a film at that time.

I’ve known you since we were children. We’ve been friends for so long, and we’ve had a lot of both shared and different experiences, especially in terms of you being a child of one of the group’s leaders and me not.

Going back to one of the things we talked about earlier, I was worried about what the process of making this documentary would mean for you. I think I had already processed a lot of my understanding of the group, and that didn’t change a lot throughout the filming. But I had an understanding in 2013 that’s very similar to the understanding that I have now.

But I could see that you would be going through a lot, in terms of adjusting to a new view of the past. So I was concerned for you as a friend. But I also felt like there was this need of an accurate portrayal of things.

Also, in terms of reaching out to people, I felt like we were in a weird situation because I was one of the first people you talked to. So I felt that if I got other people involved, I was somehow responsible for how the series works out.

I remember speaking to you on the phone at one point, Amy, and thinking that there was no way you can be objective about this. But then I debated it and realized that it wasn’t my job to convince people to participate or not.

I just felt it was my responsibility to make the series because it was a historically important thing to do, even though I knew it may be uncomfortable for me. But I knew that if I did it, it would be more likely that other people would feel more comfortable in becoming involved.

So it was something that I felt like I needed to do, even though I also knew that I would have to grapple with how much personal information I would want to share. I think this is another topic that’s very relevant for all of us – when we told our personal story, we weren’t just telling our story; we were also telling the story of everyone who we were in a relationship with in the group, whether it was parents, siblings or children. So that was a very heavy thing that I knew that I would have to navigate.

KB: I was one of the earliest people who decided to participate in the series. I had to decide if I should expose my parents, who I still have a relationship with, one of whom is very anti what happened. I asked myself, do I stir up those tensions and fight back as an adult? I also knew that the silence around it was traumatic itself.

As a child, I was put into the newspaper, but I didn’t get to have my own voice. So, like Jesse, I felt like the most responsible thing I could do for myself was to participate. I tried to say that to other people, and sometimes it worked, and sometimes it didn’t.

But I’m not sure if I would have kept participating as much if it had not been for my relationships with Jesse and Keith. Due to the difference in age, we were around each other as kids, but not as close.

Jesse and I grew up as friends to leadership kids, which was a very hard dynamic to have. The fact that Jesse had similar emotional experiences as I did was very affirming to my own story.

So to me, there was something that was healing about participating, as we’re now good friends. We text separately and all together, and meet at other Jewish delis.

There may be tensions with my family now. But no longer living in silence and denial is more important than those tensions.

Amy Siskind (AS): Having experiences in the group as both a child and an adult, the thing about the children was that there were so many things that they weren’t told. I was five-years-old when my mother got involved.

Answering this question is hard, but I wanted to emphasize that the silence was impossible. That’s why when I got into grad school, I felt like I had to write about it. A lot of it was for myself, but it wasn’t all for myself. A lot of it was also for the other children.

So for me and my brother, who died from suicide – which I attribute a lot to the ideology to the group that my mother followed – I felt very strongly about opening it up and telling the truth. I felt people should know about the group, and enter into a debate about what was good and bad…It’s very important for children to know the truth

Q: Once filming was complete on the docuseries, how did you approach editing the footage into the four episodes?

LM: Originally it was going to be a film and all of the stories were going to be told in one narrative. But then the project turned into a series. You can see in the first episode what the group was. The historical story is very chronological across the four episodes.

The other episodes also chronicle the evolving stories of how the former members are still processing what went on. These contemporary stories involve many different people who have things play out in the “present.” Those stories are woven throughout the series.