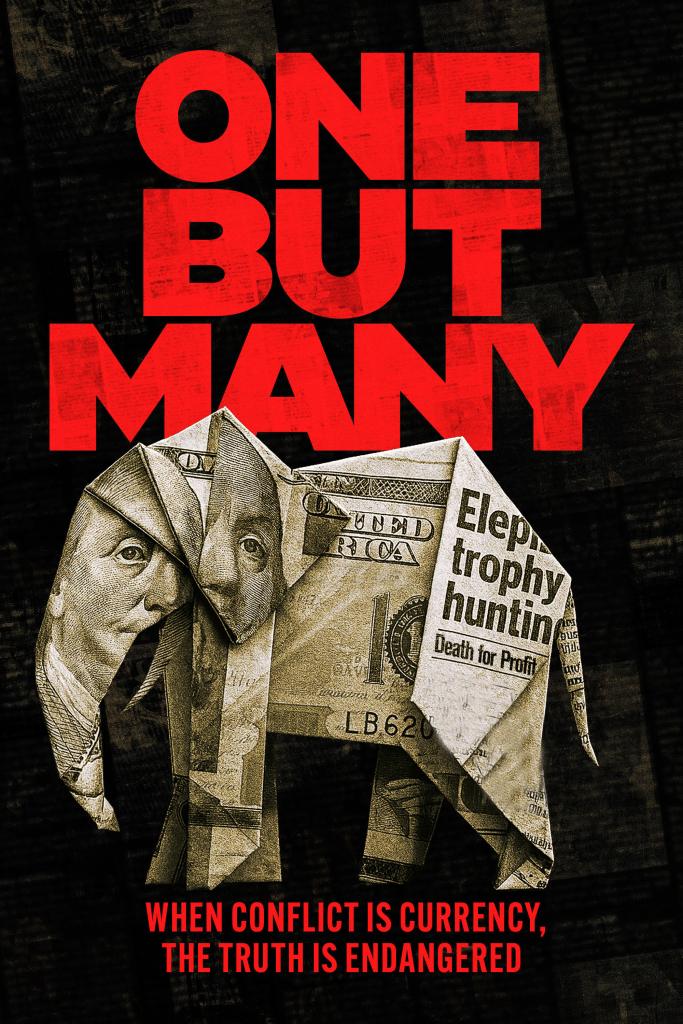

Exposing the truth about tumultuous situations to the world can often offer radical hope that the situation can positively evolve over time. The new documentary, ‘One But Many,’ dares to reimagine how people and animals share space in an increasingly complex world in order to help the human-wildlife conflict from being politically weaponized.

The project marks the directorial debut of filmmaker and activist, Janna Giacoppo. The conservationist, who’s the founder of Human Wildlife Project, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit dedicated to supporting community-led human-wildlife conflict solutions worldwide, also served as a producer on the movie.

‘One But Many’ is having its World Premiere today, Sunday, June 29 at 2:30pm PT at the TCL Chinese 6 Theatres in Hollywood during Dances With Films: L.A. Freestyle Digital Media has acquired the distribution rights for the documentary, and will release the feature after its festival run.

‘One But Many,’ which was shot on location in Kenya and beyond, reveals how the escalating global crisis of human-wildlife conflict is being weaponized against the very people and animals it affects most. The documentary exposes the deep ties between the trophy hunting industry and policy decisions driven by both the U.S. and individual African governments, leaving communities and wildlife in peril. But in parts of Kenya, where trophy hunting has been banned for decades, extraordinary models of coexistence are not only emerging – they’re thriving.

Giacoppo generously took the time earlier this month to talk about helming and producing ‘One But Many’ during an exclusive interview over Zoom. Among other things, she discussed how shooting a photo series at the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust in Kenya inspired her to make a documentary about the human-wildlife conflict. The filmmaker also mentioned how honored she is that the project is premiering at Dances With Films.

Film Factual (FF): You wrote the new documentary, ‘One But Many.’ What inspired you to explore how the escalating global crisis of Human-Wildlife Conflict is being weaponized against the very people and animals it affects most in the film?

Janna Giacoppo (JG): It actually started as a photo series almost seven years ago. I had gone to Kenya for a photo assignment. I randomly spent a day at the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust, which is where they rescue the baby orphan elephants. I’m just a researcher by nature, and was asking about this story. All the keepers who work with them just kept citing human-wildlife conflict.

So that was at the beginning of this work trip, so I kept asking questions. Everyone in Kenya who I asked what their biggest challenge was with wildlife said human-wildlife conflict. So that‘s what sparked the movie, because I realized this issue is so much bigger than I had been reading about and seeing in films.

Then several months later, Botswana had a new president coming in. He had announced that he was considering lifting a hunting ban on elephants that had been in place for a few years. Five months prior to that, the U.S. had lifted an import ban that had been issued under Obama to ban imports of elephant and lion trophies.

So the investigator in me went, wait a second. One ban is lifting as another one is lifting, so is there a connection? The big takeaway was that in Botswana, the president was citing human-wildlife conflict as the reason to lift this ban.

So this project began as a photo series, as I’m a professional photographer. As I put that together, I instantly knew that it also had to be told on screen, as a photo series wouldn’t be enough.

FF: Speaking further about the human-wildlife conflict, how did you research the topic before you began production on the movie?

JG: That process was extensive. It was kind of ongoing for several years. It started as a deep dive into the topic. I began reading as much as I could.

I also reached out to experts in conservation, and tried to get as many perspectives as I could. I mostly reached out to experts in Africa because I was looking at this issue in Africa versus the conflicts we have with wildlife here in the States. I was really interested in the United States potential influence.

But the research process really took many years. What would often happen was that I would be working on the story with my editor after having filmed some sequences.

Then I would want to speak to another person to ask them one question to clarify. That would open up a whole new rabbit hole that would then reshape our edit and reshape more filming.

I actually cut and finished the film twice. It was initially finished about three years ago. I had started submitting it, and we had some interest. But I realized there was more we had to explore. So I literally pulled it and restarted the post-production process and filmed some more.

So to your question of the research, I feel like it truly is ever-evolving. Tou can almost never stop researching with this subject.

FF: While you were filming, were there any particular experts who you wanted to speak with about the human-wildlife conflict? How did you decide who you would ultimately interview for the documentary as well?

JG: That’s a great question. To be totally frank, at first, I wanted to talk with anyone who was a leader in conservation in Kenya. It’s doing a lot in community conservation in these ways that are really innovative and inspiring. They’re also a little unknown if we look at it in terms of how many people are aware of these solutions.

So I was focused on Kenya for the experts I wanted to talk to, and that was really challenging. I think that one of the hardest things about being a documentary filmmaker is that unless you’re maybe an Oscar winner, people won’t necessarily even respond to your emails.

So getting anyone to want to speak with me, and then figuring out resources to talk with them, was maybe the hardest thing. Sometimes when I asked people if I could interview them, they would say, fine, we’ll do the interview, but we have to do it right now. But we’d be in a tiny room with bugs chirping and rain pouring. My one DP would try to get a shot, but it was terrible coverage, but we’d just need to get the interview.

So, like I said, I was hoping to speak with leaders and organizations there. I tried to focus on people who had been doing it for many years

FF: Speaking also of the cinematography, how did you determine how you wanted to visually shoot the film?

JG: Again, we took what we could get because we were thrown into a lot of guerrilla-style interviews. So I then went back and wanted to reshoot some of them. So, we took what we could get, and then tried to capture as much B-roll as possible.

The challenge, I would say, with this subject is that we were a low-budget, very grassroots indie film that was scrapping each step of the way to get the story finished. You obviously wouldn’t want to stage human-wildlife conflict. You can’t predict when it will happen, and if you could, you would obviously be trying to help prevent it.

So that ended up leading me to partner with organizations like Mara Elephant Projects, Lion Guardians and Cheetah Conservation Fund. I was trying to make inroads with them so that they could become filming partners in a way

That gave me access to a lot of their archival material. If they’re using helicopters to try to push a herd of elephants out of a village, either I was with them filming, or they were saying, “Hey, we just got this footage, do you want this?”

So it was a lot of relationships because of the nature of conflict with wildlife. You can’t, and wouldn’t want to, pre-plan that.

FF: Speaking about the archival footage, how did you decide which images or clips that you wanted to use in ‘One But Many?’

JG: So, on my second go-around with the film, I worked with Jill Oliker, in Boston, and Rob Kirwan. They’re longtime frontline BBC/PBS stock editors and writers. They were really instrumental in saying, “I think we need something here that includes a little bit more of what we’re seeing.” They also asked, “Can you talk to Cheetah Conservation Fund?”

So they really helped me, as a first-time documentary filmmaker, shape that. Then I would literally be reaching out, trying to get that footage. Or we’d say, “Okay, wait, I’ve got that footage.”

I shot most of the B-roll, I’d say. Sometimes I’d get lucky, where I’d be in Zambia, and we needed an elephant doing something. So we’d go back and we’d put it back in. (Giacoppo laughs.) But Rob and Joel were really helpful with that.

FF: ‘One But Many’ marks your feature film directorial debut. How did you approach making the movie as a first-time helmer?

JG: This is the hardest thing I’ve ever done by galaxies. Nothing comes close to it. But I think the hardest piece of the filming process as the filmmaker was telling the story I wanted to tell. But I didn’t know how I was going to tell it.

That was the question, because there were all these moving parts with the governments, and finding the right solutions. Initially, I hoped it could be a documentary series, so we could really spend time telling the story.

But we were working on it during the pandemic. So the reality of getting a series at the time was challenging.

So I just wanted to get the message out there. So we decided to turn it into a feature.

But it was emotionally challenging to go through so much really difficult data, images and videos. So I’d be crying in the middle of the night editing to find five seconds of a clip that we wanted to use. So I’d say contending with the emotional piece of the subject matter was the hardest part of the filmmaking.

FF: Besides directing the documentary, you also served as one of the producers. What was your experience like working with your fellow producers?

JG: Producing was the hardest of all. Maya Moravec was the main producer from day one until today. We had a lot of people on the team, as you can see with the names on the screen, and the film would not be here without them.

I have such a respect for producers. I think it’s the hardest job during the production. It’s really fulfilling, but I’d say it’s 100 times harder than being the director.

FF: ‘One But Many’ is having its World Premiere (this afternoon,) June 29 at Dances with Films: LA. What does it mean to you to be able to premiere the feature at the festival:

JG: To be honest, this feels like the first kind of fun part of it. Everything else has felt like an uphill battle. So it’s very surreal to think we’re going to be sitting there and watching it with an audience.

Hopefully it will then go into the world. The whole reason I told this story is because I felt so strongly that it was something that wasn’t just about wildlife in Africa. It was also about this global issue. It’s ultimately a story of hope.

It’s not just what we do to people or animals; it’s what we do to everything. What we do here has an impact across the streets and the ocean.

So the heart of the film for me is the fact that we can coexist and thrive together, whether it’s with your actual neighbor, or it’s a furry animal neighbor. But we just aren’t really shown those ways. We don’t really talk about that yet as much.

So the idea that, after all these years, we’ll be sitting in the theater during our premiere at Dances With Films is amazing. We’ll be with people who might not know anything about it going into the screening, and then might walk out of the theater with a different perspective or with questions. That’ss overwhelming in the best kind of way.